Painting & drawing blog

A REVIEW OF ‘HOW TO DRAW’ BOOKS

Learning to draw portraits for beginners

An review of Drawing Portraits: Faces and Figures by Giovanni Civardi, Draw Faces in 15 Minutes by Jake Spicer and Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain by Betty Edwards. There are no sponsored product links in this article.

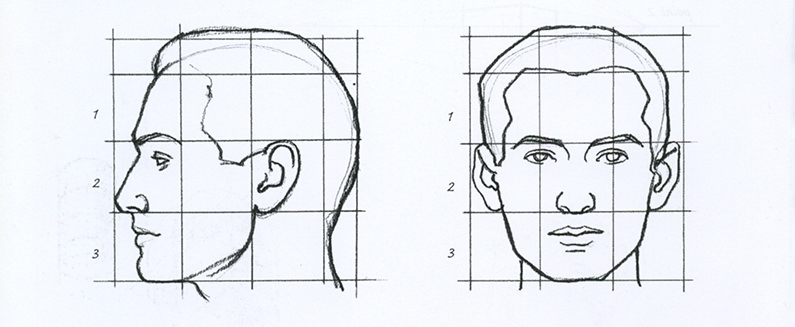

Photo credit: Giovanni Civardi, Drawing Portraits: Faces and Figures, Phaidon Press 1994

There are a multitude of ‘step-by-step’ guides to sketching the human face or figure. To be honest, I’ve always had my doubts about how useful they are because they so often focus heavily on physiognomy, and on diagrams aimed at teaching you the ‘standard’ proportions of features and bodies.

Of course, there is a long tradition of artists studying anatomy that goes back to at least Leonardo da Vinci and so I don’t want to claim that learning about the human figure is a total waste of time! In the past when artists produced huge historical or biblical paintings of full length figures in action and could use models only for their preparatory sketches, knowledge of human physiognomy was very important.

My concern however is that if we teach beginners today simply to look for formulas, they will end up ‘imposing’ these proportions onto the subject they are drawing rather than honing their own observational skills, which are so important. Whilst a face will largely conform to the proportions of a diagram like that above, there will always be slight variation from person to person and these tiny variations can make all the difference when trying to achieve a good likeness. If a head is tilted on an angle in any direction, this will also affect and alter the proportions that you’ll actually see in front of you.

Thanks to this prejudice of mine which has lead me to believe that books filled with pictures of skulls and muscles are of limited use, in the past there has only been one book I’ve recommended: Dr Betty Edwards’ hugely successful 1979 bestseller Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain which has been repeatedly revised and updated and is still very influential. I’ve always been quite evangelical about this book because it takes a fundamentally different approach and doesn’t teach a prescriptive drawing method: instead it teaches you how to LOOK.

I last read the book as an art student, so here I’ve re-assessed it from the perspective of someone who’s now been drawing professionally for many years. I’ve also taken a look at a couple of other very popular ‘how to draw’ books on the market to see if there were other useful approaches out there that I would recommend to a beginner.

GIOVANNI CIVARDI, Drawing Portraits: Faces and Figures, Phaidon Press 1994

Giovanni Civardi is the author of a number of drawing manuals, including another hugely popular book entitled The Art of Drawing: Heads and Faces. The book I’ve chosen to review here was published in 1994 and is also a very big seller. Civardi is unquestionably a very talented artist, however Drawing Portraits: Faces and Figures felt like a classic example of the type of book that I have issues with. The problem is a general vagueness throughout. The book is aimed mostly at learning to draw by observing a live model, and in an early (and very brief) section called ‘How to get a likeness’ Civardi says the following:

‘To achieve a physical likeness pay particular attention to the overall shape of the head (drawing ‘from the general to the particular’) and exactly evaluate your subject’s proportions, both in the face as a whole and between its elements (eyes, nose, mouth etc). To achieve a psychological likeness, converse with your model, try to understand their character, preferences, habits and observe the environments where they live and work’

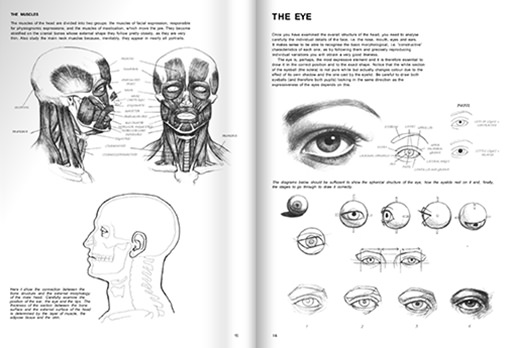

Photo credit: Giovanni Civardi, Drawing Portraits: Faces and Figures, Phaidon Press 1994

I can’t really imagine this non-specific advice being of much use to a beginner who lacks experience, and probably also confidence – it’s much too general.

In the next chapter which is called ‘Drawing the Head’ Civardi introduces a series of diagrams including the image above, showing various facial proportions. He notes that ‘of course, heads vary greatly in size and in the combination of characteristics, but they can all be reduced to a proportional diagram which helps to simplify the shapes, to recognise their peculiar three-dimensional aspect, and also to position details correctly in relation to one another’.

Drawing by imagining a grid is indeed a very useful way to begin breaking down and analysing the proportions of the person or object you are drawing. However although Civardi notes in an aside that you should ‘compare them with those of your model and assess whether they correspond or differ’, I’m not sure whether he hammers home clearly enough the message that rather than simply applying his formulas to your model, you should use them only as a measuring tool to assess these relationships for yourself.

The book then dedicates several pages each to individual features (the eyes, ears nose and mouth). For each feature Civardi shows anatomical diagrams teaching you the names of all their different parts and sketches of the features seen from different angles, none of which seemed very useful to me.

Of more help is a small ‘four step’ diagram for each feature where Civardi demonstrates how he initially blocks out shapes and shading before working in more detail with each step. This is all followed by a quite constructive demonstration of a whole portrait head, drawn in stages by finding axis lines, blocking in overall shapes, roughing in and then refining shades and tones.

The remainder of the book is filled with varied examples of Civardi’s highly accomplished drawings. He has a wonderful loose hatching style and the drawings do have a value is demonstrating a range of different types of mark making and sketching styles that you could copy and experiment with. However whether they would inspire or intimidate a beginner I’m not sure – maybe a little of both. I’m just not certain that Civardi’s book provides you with the necessary tools to try to emulate him.

JAKE SPICER, Draw Faces in 15 Minutes, Ilex Press, 2016

Jake Spicer is a fantastic artist and a good writer. He is the author of a number of much more recent and very successful ‘how to draw’ books including titles such as ‘Draw People in 15 minutes’ and You will be able to Draw by the End of this Book’. They are all designed to be accessible and helpful to the complete beginner. ‘Draw Faces in 15 Minutes’ aims to provide a working method for completing a quick portrait sketch of a face (although as the author amusingly notes on his website ‘despite appearances, I am not fundamentally opposed to drawings taking longer than a quarter of an hour’)

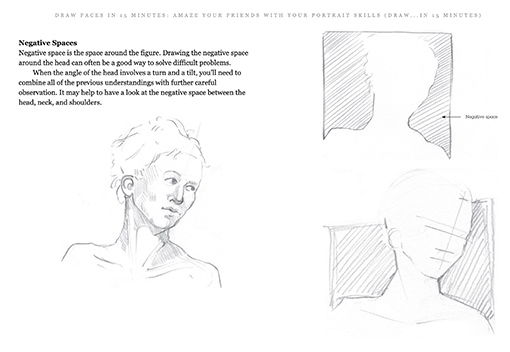

Photo credit: Jake Spicer, Draw Faces in 15 Minutes, Ilex Press, 2016

The book encourages you to sketch from live observation rather than from a photograph, and it starts from the premise that fifteen minutes is a reasonable length of time to ask a friend to pose for you. Insisting that one should practice drawing a person only from life is a bit problematic because not everyone has someone prepared to model for them, but Spicer suggests drawing people surreptitiously on trains or in cafes or simply drawing yourself in a mirror, if you have no other options. I think you could still apply his instructions to copying from a photograph however.

Whomever you draw, I think that the time restraint Spicer suggests is a nice good idea because it reduces a beginner’s anxiety and encourages them to take the plunge and just practice without worrying too much how the drawing turns out.

After some general notes on posing a model and selecting your materials, the drawing instruction gets underway with some very useful advice on how to identify the tonal range of whatever you are drawing, and which specific types of mark making or hatching you might employ to indicate those tones. Spicer is concise when discussing the basic challenges of sketching and he tackles the philosophical question of how we can abbreviate what we see in order to represent it, noting that although lines ‘do exist in the visual world they often represent an idea that we impose’ but that ‘we may choose to use a line as a way of translating and simplifying information, to represent some kind of boundary’.

Unlike Civardi’s sometimes overly prescriptive suggestions, Spicer’s book teaches you to continually check your drawings against your own observations instead of working to a formula. In a page called ‘Looking’ he gives the excellent advice to keep your eyes constantly flitting from model to paper and back again: ‘….keeping the dialog between subject and drawing fresh and immediate without the interruption of an internal critical monolog. It is this internal critic telling you your marks are wrong that can restrict drawing much more than a lack of ability. Do everything you can to remain present in the moment of drawing and to maximise the connection between eye and hand without intellect getting in the way’. This is then consolidated with exercises that demonstrate how to actually put it into practice: how to measure by eye and with your pencil, to check for horizontal and vertical relationships and to visualise negative space.

When setting out his instructions for tackling a basic portrait sketch Spicer demonstrates his ‘layered’ technique that is the basis of his method. This consists of beginning with a quick ‘continuous line’ drawing just to get something down on the page and then erasing it back and working into it: measuring the relationship between features, looking for outlines and shapes, developing those features, outlines and tones, and lastly checking all of their relationships again. It’s a helpful and specific approach that gives you a working method for putting pencil to paper and developing your drawing with accuracy. The book provides tools for drawing a face, and not prescriptions about what that drawing should look like.

DR BETTY EDWARDS, The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, HarperCollins, new edition 1999

Re-reading this book again after many years I’m struck by how different it is to every other book about learning to draw. Rather than providing sketches by the author for you to try to emulate, it’s full of ‘before and after’ portrait drawings by Edwards’ students that shows you their quite astonishing improvements after undertaking the exercises she promotes. Edwards does not separate the individual features of the face and devote a section to showing you how to draw each one: indeed the whole book is premised on the idea that the less you mentally isolate and ‘name’ any feature as you draw it the better you will do so. This particularly applies to the features of the human face the author notes, because in childhood we develop extremely fixed ideas (or ‘symbols’) for how we should draw them.

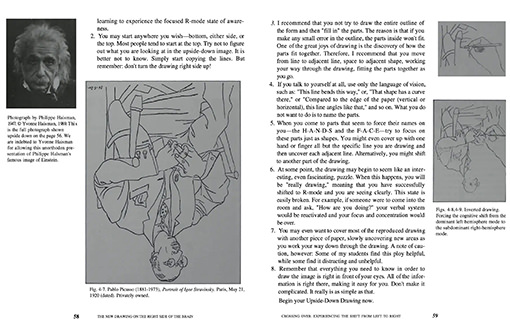

Photo credit: Betty Edwards, The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, HarperCollins, 1999

Essentially the book is geared around one big central theory, which concerns two different modes in our brain that can be activated as we interpret what we are looking at. Drawing isn’t a mysterious and magical talent, Edwards asserts, that is restricted to those people we regard as having that rare artistic ‘ability’. Artists are simply people who understand instinctively how to switch to the correct brain mode, and therefore don’t need to have it explained to them. She writes encouragingly in the introduction that “you will soon discover that drawing is a skill that can be learned by every normal person with average eyesight and average eye-hand coordination”. Her book isn’t even really about teaching drawing skills, Edwards says, but is about teaching perception.

The book is quite long and initially spends a lot of time explaining Edwards’ theories (she has a doctorate in Art, Education, and Psychology) but I do recommend that you read all of this because it’s well written and comprehensible, and will help you understand the point of the exercises that follow. Edwards’ research was triggered by a particular class teaching her high school students to draw, in which on impulse she turned a copy of a line drawing by Picasso upside down and asked them to copy it. The all did so with great accuracy, but when they repeated the exercise with the original drawing the right way up they struggled to achieve a similar likeness. Edwards asked herself why on earth this would be so, and her question lead her to the late-sixties research of a psychobiologist named Roger W. Sperry into the spheres of the brain, and their different types of activity.

Sperry posited that the two sides of the brain employ different modes of perception: with the left side interpreting sensory information verbally and analytically (using words to name, describe and define what we are seeing) whilst the right side does so in a purely visual, perceptual and simultaneous way. We process the world largely with the left side of our brains, Sperry believed, analysing everything that we experience in a linguistic fashion. To Edwards this was a breakthrough in her understanding: she realised that when we try to draw a face our left brain (the ‘L-mode’ as she abbreviates it) takes over and starts to filter what we are seeing through long-held perceptions about what something ought to look like. Only when we stop doing this and use our right brain (R-mode) to appraise the edges, spaces, shapes and relationships within our subject, can we learn to draw with accuracy.

Since Sperry’s original research our understanding of the activity within different parts of the brain has developed greatly, and the left/right division turn out to be not as clean-cut as Sperry initially thought. However as Edwards herself says in this updated edition of her book, the literal location within the brain isn’t really important: what matters is that there have indeed been proven to be two separate and distinct cognitive modes by which we can take in information. ‘Left brain’ and ‘Right brain’ are simply convenient metaphors to differentiate them.

Reading this book as an art student was a ‘lightbulb’ moment for me too, because I realised that I completely recognised this cognitive ‘shift’ and being in a slightly altered state of consciousness when I was drawing well: unaware of time, and unburdened by anxiety. When things were going wrong and I was during with less accuracy it was precisely because I was allowing my verbal brain to dominate and focus too much on what I was drawing.

How can the beginner be taught to recognise when they are being inhibited by using the left side of their brain, and learn to bypass it? Edwards realised that the way to do this was to create exercises that disrupt the left side’s ability to ‘jump in’ and try to help us. If we try to copy a drawing upside down, we cannot really recognise the forms that we are seeing and cannot identify or mentally isolate particular features. We can only see an abstract collection of lines and shapes and the only way to reproduce them is by paying proper attention to them without preconceptions.

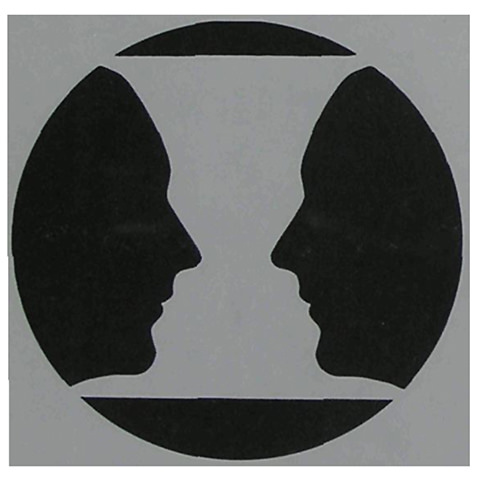

An initial exercise that Edwards gives exemplifies the point. Here she sets you a copying challenge, to reproduce one of those ‘optical illusions’ that can been seen either as a vase or two faces seen in profile. She asks you to note whether this is easier and more successful when viewing the drawing as a random vase shape where you need to really study the shape of the line in order to copy it, or when you think of it as trying to reproduce two face profiles. The latter, she suggests, will probably feel much more difficult.

Photo credit: Betty Edwards, The New Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, HarperCollins, 1999

The rest of the many exercises in the book are all designed to practice this shift between the two modes of looking, until you’ve really grasped the principle. The exercises involve drawing not just people but often objects or other artworks, sometimes employing a little homemade viewfinder. Edwards does eventually spend a considerable amount of time showing proportional diagrams of the head, but only as a means to teach you how to measure for yourself, and to avoid common errors and misperceptions caused by not really looking.

Initially it felt very counter-intuitive to me to be asked to see a face simply as a collection of forms and to allow myself no emotional response to it, because of the way we are always taught that drawings should be ‘expressive’. However her method undoubtedly really does work, and I think in fact that the more confident, accurate and uninhibited your drawing becomes as you master her technique, the more you have a freedom to control your mark making and can produce more naturally expressive work.

If I were to buy only one book on how to draw people, I think it would still be Edward’s. If you can buy two then go for Jake Spicer’s excellent book as well, but read Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain first. Although Spicer’s book will certainly improve your drawing and presents a helpful and easy-to-follow working method for tackling a portrait, much of his general advice simply expresses a version of the theory elaborated in Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. I think that only the latter book will improve your drawing fundamentally, and perhaps beyond recognition. Of all of the books I’ve looked at it will give you the most confidence to believe that drawing well is an attainable skill for you too, and for a beginner this really is the most important message to hear.

CATEGORIES

DRAWING PEOPLE

DRAWING ANIMALS

DRAWING MATERIALS

OIL PAINTING

WATERCOLOUR

PAINTING MATERIALS

FRAMING